Two days “to treasure whales” in Niue

August 2016

It’s dawn on our first wake up in Niue. I clamber to the cockpit, wrapped in a Turkish towel for a blanket and feeling the after-effects of just a bit too much “hooray-we-made-it” celebratory rum.

I’m hoping to spot a whale or two, and I do, far in the distance. –Jessie

When we departed Suwarrow in the Cook Islands, we had a choice: sail west to Samoa or southwest to Niue. We opted for the latter. Niue (New-way) is one of the largest uplifted coral islands on the planet and, because of its topographic uniqueness, has a dramatically different vibe than the rest of the South Pacific. Palm-strewn beaches are replaced by 20-meter vertical fortress cliffs, and a reef juts from the base of the walls, a coral mote encircling the entirety of “The Rock.”

When we departed Suwarrow in the Cook Islands, we had a choice: sail west to Samoa or southwest to Niue. We opted for the latter. Niue (New-way) is one of the largest uplifted coral islands on the planet and, because of its topographic uniqueness, has a dramatically different vibe than the rest of the South Pacific. Palm-strewn beaches are replaced by 20-meter vertical fortress cliffs, and a reef juts from the base of the walls, a coral mote encircling the entirety of “The Rock.”

Unlike most islands where the sea shoals and anchorage can be found over sand, that is not an option in Niue. Instead, “The biggest little yacht club in the world” maintains a field of moorings near the town of Alofi, the only nook on the island with a break in the reef. Each mooring is tethered to the sea floor by two 2-ton concrete blocks. We snagged one on the outside of the mooring field and were gobsmacked that the beefy blocks were easily visible 90 feet below. With no beaches to cloud the seas with sediment, Niue’s waters are pristine and the clarity surreal. Niue is not an easy place to reach. Aside from one of two weekly flights from New Zealand, sailboat is the only option, ensuring the island nation remains a secret gem in the world of tropical travels. Just as getting to Niue takes effort, so too does getting ashore from your boat.

Niue is not an easy place to reach. Aside from one of two weekly flights from New Zealand, sailboat is the only option, ensuring the island nation remains a secret gem in the world of tropical travels. Just as getting to Niue takes effort, so too does getting ashore from your boat.

We launched Miss Sassy and made our way toward an austere concrete wharf, landbound for the first time in nearly a week. We had been forewarned about the one-of-a-kind landing situation and arrived with a few nerves of anticipation. I leapt from the dinghy at the foot of concrete stairs that disappear when the tide is high. I rushed to the top of the stairs, where I grabbed a gigantic remote as Neil tilted our outboard and readied a three-point harness, which he’d affix to a large yellow hook that I was to lower to him. I was thankful a local person was nearby to assist, as our little Hypalon boat and the good Cap’n were hoisted some 10 feet into the air! Suspended above the water, I deposited the remote into its holster and scurried to tug my little boat (and husband!) to safety using a line that tangles from the top of the crane.

Next, we unloaded Miss Sassy onto a flatbed dinghy trailer and offloaded her between two painted yellow lines, a parking lot right-sized for tenders. In much of a swell, getting ashore would be tricky if not downright dangerous and would surely be amusing to watch. We would learn later that leaving shore after dark was not much fun.

We were greeted warmly by the Niuean agents from Customs, Immigration, and Biosecurity, and—thankfully—the clearance process was costless and far simpler than getting the dinghy to shore!

Oma Tafua

Aside from the novelty of the topography and the exclusive access to the remote island nation, we were enticed to Niue by the opportunity to assist with humpback whale research. Marine biology is a far cry from the research I conduct in my landlubber life, but the thought of contributing to science and supporting ocean-related research exhilarated me. Neil was just as keen and when we saw a poster in Tahiti recruiting westbound cruisers to volunteer their sailboats in Niue, we emailed our interest immediately!

Niue is home to Oma Tafua, a not-for-profit founded a decade ago by Fiafia Rex, a local person whose heart beats for ocean. O ma Tafua translates to “to treasure whales.” Dwarf minke whales, sperm whales, humpbacks, and spinner dolphins (potentially a unique subspecies endemic to the area) are among the marine mammal species that have been documented in Niuean waters. Although the organization documents the presence of marine mammals, humpbacks are its greatest muse.

ma Tafua translates to “to treasure whales.” Dwarf minke whales, sperm whales, humpbacks, and spinner dolphins (potentially a unique subspecies endemic to the area) are among the marine mammal species that have been documented in Niuean waters. Although the organization documents the presence of marine mammals, humpbacks are its greatest muse. The operation runs on a shoestring and lacking their own boat, relies on visiting yachts to get out onto the water when humpbacks visit between July and September. We were honored to volunteer Red Thread to support their mission. For two days, Fiafia was our teacher, offering us one of the most precious learning experiences on our voyage. Our tasks were three-fold:

The operation runs on a shoestring and lacking their own boat, relies on visiting yachts to get out onto the water when humpbacks visit between July and September. We were honored to volunteer Red Thread to support their mission. For two days, Fiafia was our teacher, offering us one of the most precious learning experiences on our voyage. Our tasks were three-fold:

- Photograph whales

- Collect skin samples

- Record whalesong

During the 1800s, many whale species were hunted nearly to the brink of extinction as they travelled between their feeding and breeding grounds. An estimated 250,000 humpbacks were killed before the International Whaling Commission placed a moratorium on commercial whaling in the 1960s. Their numbers have slowly made a comeback in the last half-century, though they remain below their pre-whaling estimates. Much remains to be learned about the movement of humpback whales in the southern hemisphere, and the work of Oma Tafua contributes to both the generation of knowledge and the conservation of these beautiful creatures.

A whale of a time

A whale of a time

At 7 am, Neil roared off to retrieve Fiafia and another Oma Tafua team member from the wharf, as well as our friends Mike and Gill from s/v Romano, who we were delighted to see for the first time since Raivavae in French Polynesia. As a crew of six, we left Miss Sassy dangling on our mooring, so as to keep our bow, an ideal spot for scouting, clear. We had blue skies and a soft breeze, lovely conditions for what would turn out to be nine hours of excitement, laughs, and learning.

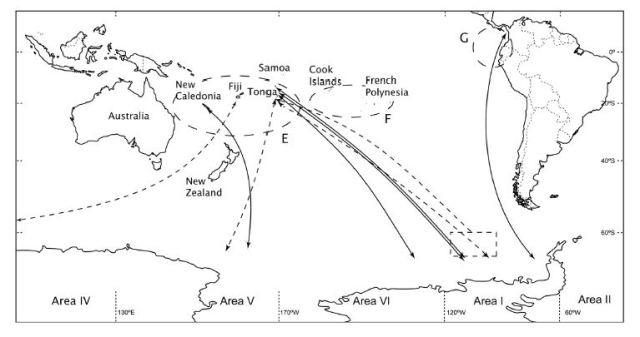

Each year humpback whales complete one of the longest migrations of any creature on earth, journeying some 6,000 miles (10,000 km) from Antarctica to calve and breed in the warmer waters of the South Pacific during the southern hemisphere winter. Antarctica is broken into six feeding areas (I-VI) and research using photo identification and geolocation tagging technologies has indicated the presence of relatively established migratory corridors and the tendency for individual humpbacks to travel to and from particular feeding and breeding areas with some consistency. More specifically, a series of breeding grounds dots the South Pacific—Australia, New Caledonia, Tonga, Niue and the Cook Islands, and French Polynesia—and generally attract the same whales year after year, though there is some evidence of individual movement between South Pacific islands.

This figure shows “migratory connections of humpback whales between breeding grounds of Oceania and the eastern Pacific, and feeding Areas of Antarctica” (p. 655). It was published in a 2018 paper in Polar Biology by Steele and colleagues. The full-text article is freely accessible by clicking on the image.

As we angled Red Thread’s bow toward the open ocean, Fiafia instructed us to watch for spouts (also called “blows”) and “footprints” or glassy sections of water that might indicate movement just below the surface. Less than 10 minutes passed before we had our first sighting of the day!

We learned that the angle at which a humpback dives will give some indication of whether they will surface again soon or whether they intend to remain submerged for a longer period. If you see their fluke (i.e., tail), you can expect that they are diving deep and likely won’t surface for 20 minutes or longer. If the angle is softer, they may be on the move (“a traveller”) or intending to surface again shortly.

We learned that the angle at which a humpback dives will give some indication of whether they will surface again soon or whether they intend to remain submerged for a longer period. If you see their fluke (i.e., tail), you can expect that they are diving deep and likely won’t surface for 20 minutes or longer. If the angle is softer, they may be on the move (“a traveller”) or intending to surface again shortly.

Interestingly, a humpback’s fluke is as unique as a fingerprint, making it the key to photo identification. Thus, although photos from any angle were special, capturing a crisp image of a fluke was particularly special and meaningful for Oma Tafua’s work.

Humpback facts 101

Humpback facts 101

The gestation of a humpback is 11 months, so a winter romance in the South Pacific means giving birth in the same waters the following year. While in the South Pacific, these whales don’t feed; all energy is devoted to matters of birthing and baby-making. It seems an otherworldly feat to swim 6,000 miles heavily pregnant to birth a 15-foot (4.5-meter), 1.5-ton baby that will demand 158 gallons (600 liters) of milk daily, all the while knowing you will have no meals for months.1

Most females calve every two to three years, but some give birth in consecutive years, meaning that there is nothing to stop males from pursuing a mother with a newborn. This can make for a precarious situation for a newborn calf, particularly if multiple males attempt to pursue its mother simultaneously. The competition to breed is a spectator sport above the water just as much as it must be below. Larger than our sailboat, the 30-ton beasts slap their 6-foot (2-meter) pectoral fins and lob their tails communicating flirtation or expressing guardedness. And they breach, catapulting their gargantuan bodies out of the water in a stunning demonstration of athleticism, for which all evidence is absorbed by the sea in seconds.

When whales breach (for purposes related to breeding, cleaning, or play), they leave skin cells on the surface of the water. They float for but a few minutes, so after each breach we throttled closer to attempt to skim the water with a very high tech skimming device: a tightly woven mesh pasta colander affixed to a broom handle. Despite our efforts, we didn’t have success collecting any skin cells, mainly because Red Thread is simply too slow to get to the breach site before the cells sink, while also maintaining a safe distance while the breach is occurring.

When whales breach (for purposes related to breeding, cleaning, or play), they leave skin cells on the surface of the water. They float for but a few minutes, so after each breach we throttled closer to attempt to skim the water with a very high tech skimming device: a tightly woven mesh pasta colander affixed to a broom handle. Despite our efforts, we didn’t have success collecting any skin cells, mainly because Red Thread is simply too slow to get to the breach site before the cells sink, while also maintaining a safe distance while the breach is occurring. Although female humpbacks may produce some vocalizations, it is males who are the singers. We spotted a fluke, and as the whale dove, Fiafia exclaimed, “I think that’s my singer!!” We throttled into neutral allowing Red Thread to bob. The sun was high and the water peaceful. She pulled on her headset, plopped onto the swimstep, and fed a microphone off our stern. Ten meters below the surface, the microphone dangled in the water column. None of us uttered a peep, as we watched a smile spread across her face. “It’s him.”

Although female humpbacks may produce some vocalizations, it is males who are the singers. We spotted a fluke, and as the whale dove, Fiafia exclaimed, “I think that’s my singer!!” We throttled into neutral allowing Red Thread to bob. The sun was high and the water peaceful. She pulled on her headset, plopped onto the swimstep, and fed a microphone off our stern. Ten meters below the surface, the microphone dangled in the water column. None of us uttered a peep, as we watched a smile spread across her face. “It’s him.” We shut off the engine and drifted for nearly half an hour, taking turns swooning over one of nature’s most melancholy love songs (listen to the recording on Soundcloud!). Singing is believed to be important in mating processes (and perhaps other communications, too). Neil tugged on his mask and snorkel, eager to listen through the water, rather than Fiafia’s headphones. Having forgotten his own swimming suit, Mike, the proud Scot, donned Neil’s star-spangled boardshorts so that he too could join. The want to hear whale song was more important than national pride at that moment! The two grown boys bobbed side-by-side holding onto the swimstep as delighted as children!

We shut off the engine and drifted for nearly half an hour, taking turns swooning over one of nature’s most melancholy love songs (listen to the recording on Soundcloud!). Singing is believed to be important in mating processes (and perhaps other communications, too). Neil tugged on his mask and snorkel, eager to listen through the water, rather than Fiafia’s headphones. Having forgotten his own swimming suit, Mike, the proud Scot, donned Neil’s star-spangled boardshorts so that he too could join. The want to hear whale song was more important than national pride at that moment! The two grown boys bobbed side-by-side holding onto the swimstep as delighted as children!

Perhaps most fascinating, Fiafia discussed recent evidence that humpbacks’ songs pass between the various breeding populations across years, meaning that the songs heard on the eastern coast of Australia might be heard in New Caledonia or Tonga in subsequent seasons. It is still not known where this sharing of songs occurs, though some have speculated it may occur in areas, such as the Kermadec Islands between New Zealand and Tonga, where tracking data have revealed that several populations converge during their migratory routes. Back for more…

Back for more…

We returned on Day 2, this time just Fiafia, Neil, and me. We opted to circumnavigate the island, heading counter clockwise around the island toward its rougher eastern coast. Red Thread slammed uncomfortably through the seas for a couple hours, our Yanmar engine forcing us through 2-meter waves. It wasn’t comfortable and we saw fewer whales than on Day 1, but the coastline was stunning! It was overcast part of the time and the breeze felt a bit chilly. Committed to not missing any potential sightings, Fiafia remained on the bow, even as I retreated to the cockpit, where Neil stood at the helm. Midway along the eastern side of the island, we saw a blow with a shape that differed from others (shapes differ by species due to positioning of the blowhole). A sperm whale, Fiafia informed us.

As we rounded the northern tip of the island, returning to the lee and calmer water, the action picked up. There were single whales and small groups. Spouts, spouts, spouts. Breaching, slapping, breaching. Flukes. And then silence. Rinse and repeat.

As the afternoon waned and we were motoring back toward the Alofi, a whooshing breathe exploded just a few meters to port of our floating home, which suddenly felt rather small. A newbie to Niue

A newbie to Niue

Several days after our research adventure, Fiafia had finished combing painstakingly through the thousands of photos we had over those two days. She shared the exciting news that we had photographed a whale never catalogued in Niue’s waters, and she invited us to name him/her! We decided to call the one-of-a-kind creature “Kaga” the first to letters of our mothers’ names (Kay Dell and Gail). In Niuean, the pronunciation is “Kanga.” Our photos simply do not do it justice. If you’d like to see a bit of Oma Tafua footage of a mama and her newborn babe, click here. Thank you, Fiafia, for teaching us so much and for making your life’s work protection of these beautiful creatures.

Our photos simply do not do it justice. If you’d like to see a bit of Oma Tafua footage of a mama and her newborn babe, click here. Thank you, Fiafia, for teaching us so much and for making your life’s work protection of these beautiful creatures.

1Given that this blog is years delayed and I have now given birth myself, the feasibility of this act is all the more implausible. After giving birth, I could scarcely go two hours without a snack (usually something decadent and ridiculous, like an ice cream-laden double chocolate brownie).

Enjoyed reading your post, even if it is from 4 years ago. As we sail north on Anui following the Humpback Whales migration, it is nice to read about your experience.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you for reading and for taking a moment to comment. This blog is a labor of love, and I wish I wasn’t still playing catch-up! That said, had I posted this years ago, perhaps you wouldn’t have ever stumbled upon it! I look forward to following you as you follow the whales. May you get to have a few close [but not too close!] encounters with these magnificent animals! -Jessie

LikeLiked by 2 people

Pingback: Whittled by Mother Nature: The ancient sea tracks of Niue | s/v The Red Thread

Pingback: Sea serpents and engine gremlins | s/v The Red Thread

Pingback: Two fish and one existential crisis | s/v The Red Thread

Pingback: Diving with giants: A peak into Tonga’s underwater wonderland | s/v The Red Thread